ADORN

Typography & Printing

Victorian Calligraphy and

the Legacy of William Morris:

A Revival of Craft and Spirit

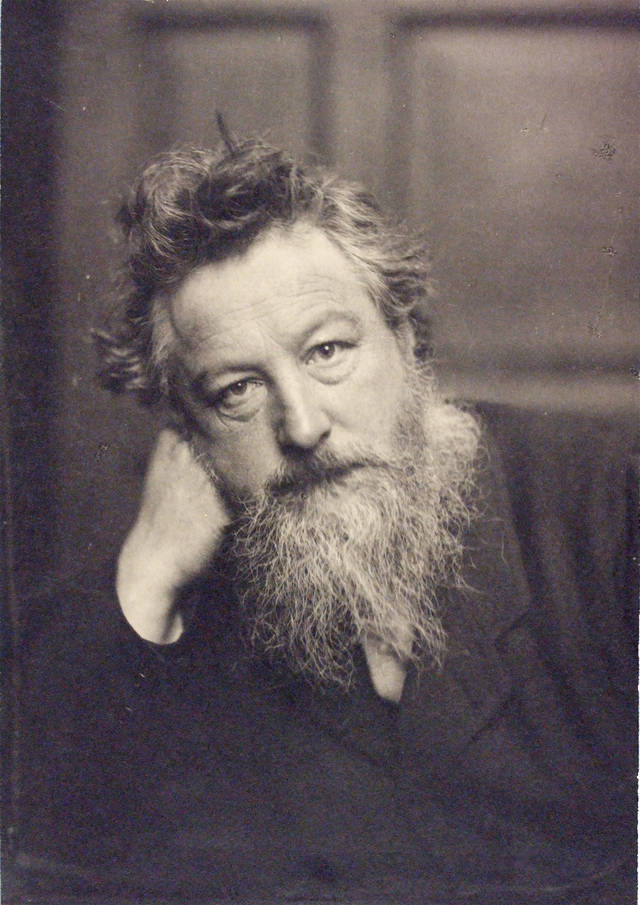

In an age when factories belched smoke and progress was measured in gears and grime, one gentleman dared to ask: must beauty be sacrificed for efficiency? Enter Mr. William Morris—designer, poet, printer, and provocateur of the prettiest kind—who turned his back on the soot-stained present and looked to the gilded past for answers.

While others chased profit, Morris chased poetry. His influence spilled far beyond the calligrapher’s desk, touching architecture, textiles, interiors, and the very notion of what art could be. At a time when mass production threatened to flatten the soul of craftsmanship, Morris championed the handmade, the meaningful, and the exquisitely human.

And where did this quiet revolution unfold? Not in Parliament, nor in the foundries—but on the page. With a flourish of ink and a reverence for medieval manuscripts, Morris reclaimed calligraphy as an art form, proving that even in the most mechanized of times, beauty could still be written by hand.

Crafting Beauty: Morris’s Calligraphic Vision

My dearest readers,

It is not every day that one encounters a gentleman who prefers gilded margins to gilded invitations, but such was the case with Mr. William Morris—artist, romantic, and self-taught scribe of no small ambition. Long before he founded the Kelmscott Press or became the darling of the Gothic Revival, young Morris found himself spellbound by the illuminated manuscripts of Canterbury Cathedral. While other boys chased cricket balls, he chased calligraphic curls and golden initials.

At Oxford, he was seen haunting the Bodleian Library—not for scandal, but for scrolls. There, amid medieval texts and monastic quiet, he cultivated a belief that would guide his life’s work: that beauty and utility should never be strangers, and that every book, every letter, every margin might aspire to art.

This notion, my dear readers, was not merely decorative—it was defiant. In an age of soot and steam, Morris looked backward to move forward. The Gothic Revival, with its pointed arches and reverence for the medieval, gave him fertile ground. Publications like Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages fluttered through fashionable parlours, but Morris saw more than trend—he saw truth. With the help of publisher F.S. Ellis, he studied rare Italian writing-books, absorbing the elegance and discipline of Renaissance calligraphy like one might absorb a scandalous secret: slowly, and with great satisfaction.

Between 1870 and 1875, Morris embarked on a project that would make even the most industrious debutante blush: he wrote and decorated twenty-one manuscript books by hand. Many featured translations of Icelandic sagas—tales of heroism and hardship from a land untouched by the smoke of industry. His travels to Iceland only deepened his admiration, and one suspects he found in its landscapes the same quiet dignity he sought in his work.

But let us not mistake his calligraphy for mere nostalgia. Morris taught himself five scripts, mastering Roman and italic forms, and gilded his initials with the same care one might reserve for a coronation. His Book of Verse, created for Georgiana Burne-Jones, is a triumph of collaboration: Morris penned the poetry and calligraphy, while Edward Burne-Jones and others added illustrations. The result? A visual sonnet, where every vine and bird sings in harmony with the text.

What sets Morris apart, dear readers, is his refusal to imitate. He studied the scribes of old not to mimic, but to converse. His decorative flourishes were never frivolous—they were chosen with intention, to elevate the spirit of the text and engage both eye and intellect.

With the founding of Kelmscott Press in 1891, Morris extended his vision to printed books, proving that even in the age of mechanization, craftsmanship could still reign. His volumes were celebrated not just for their beauty, but for their typographic innovation—a quiet rebellion in ink and paper.

And so, as we revisit Morris’s legacy, let us remember: design is not merely style—it is spirit. His work whispers across time, reminding us that the handmade, the meaningful, and the beautiful still matter.

Yours in observation and adornment,

Lady Westmacott

Leave a Reply